By Shazain Ahmed Khan and Marija Blašković

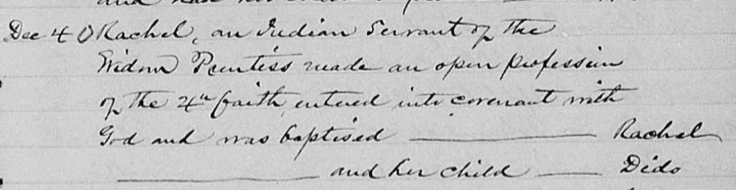

On December 4, 1720, a Native woman named Rachel was accepted as a member of the Montville Congregational Church just north of New London, Connecticut. That same day, she and her daughter, Dido, were baptized together. Rachel was noted to be the “Indian servant” of Sarah Prentiss. This seemingly innocuous record, and the language of “servant,” obscured a rather incredible story of multi-generational enslavement that dated back forty-five years.

Rachel had been born free in approximately 1665 into a Native community in the Dawnland, or New England, perhaps among the Narragansett or Mohegan, although the records are unclear. When she was around ten years old, her world was torn apart as a vicious war broke out between colonists and most of the region’s Native nations. Led by a Pokanoket/Wampanoag sachem named Pumetacom (called King Philip by the English), it was a massive war of intertribal resistance against decades of English colonization that had attempted to steal Native lands, suppress Native sovereignty, and destabilize Native communities. The colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut banded together to wage a total war against the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, Massachusett, Narragansett, and other nations.2

Colonial leaders quickly turned to the mass enslavement of Native Americans in order to terrorize them, reduce their numbers, and to fragment families and communities. Adult males were most often shipped out of the region and sold into slavery, while women and children were most commonly sold into slavery in local English families.3

In the chaos of war and slave-raids, Rachel was one of the two thousand Native Americans rounded up and sold into slavery, perhaps taken during the December 1675 raid on the Narragansett Great Swamp fortress.4 Rachel was sold, seemingly to the Prentiss (Prentice) family, likely directly to the house of John and Sarah Prentiss. John’s father, Captain Thomas Prentiss, had fought in the war. Very little is recorded of Rachel’s life after her enslavement, but she likely performed a multitude of household chores and took care of the Prentiss children. The Prentiss household contained additional enslaved people, including another Indigenous man named Richard, who was baptized in a local church (likely the Montville Congregational Church) on October 15, 1693.5

At some point, Rachel married an African man named York, who was enslaved by Alexander Pygan in a nearby household or farm. Following Pygan’s death in 1701, York was seemingly deeded to his son-in-law, the Reverend Eliphalet Adams.6 Tragically, as Rachel and York bore children, their enslavers claimed ultimate ownership over them, too. Most commonly, John Prentiss simply deeded Rachel’s children to his own children, to be held as slaves. In 1711, John Prentiss signed a document that exemplifies his legal transfer of Rachel’s children to his own progeny.;Prentiss ordered that Limone should serve his son-in-law Thomas Hosmer until she was thirty years old. He deeded Billah to another son-in-law, the Reverend John Buckley, until she turned thirty-two years old. To his daughter Sarah he gave Zilpah, who was to be free at the age of thrity-two. To his daughter Elizabeth, he gave Hannibal, who should be set free at thirty-five. To his daughter Irene, he gave Yorke, who was to serve until the age of thirty-five. Prentiss retained Scipio in his household, but promised him his freedom at the age of thirty. And the enslaved Indigenous matriarch of the family, Rachel, he deeded to his daughter Irene, notably, with no promise of future freedom.7

These calloused family separations, while common, must have been quite traumatic to the children and the mothers who experienced them. Even though there was often a promise of freedom, who was to ensure that, twenty-five or thirty years later, the paper trail would be clear enough to prove in court? Term-limited slaves like Rachel’s children could also be trafficked across colony lines or silently sold into lifelong slavery. Other examples indicate that term slavery after wars could easily turn into lifelong and even multi-generational enslavement.

Additionally, this 1711 deed transfer illustrates the way that mixed-race Native American children were re-raced as “Black” or “Negro,” with their Native identities erased. John Prentiss noted Limone and Hannibal to be “black,” with no racial designation for Billah, Zilpah, Hannibal, Yorke, or Scipio.

John Prentiss died shortly thereafter, and within a few years, Rachel was still in the household of John’s widow, Sarah. Rachel must have accompanied Sarah to the Montville Congregational Church along with Rachel’s daughter, Dido. On December 4, 1720, Rachel made a public profession of faith and was baptized and admitted as a member; Dido was also baptized that same day. Little is known about either Rachel or Dido after this event, but more than a decade later, in 1732, Dido was back in the Prentiss household as a bound servant for 4.5 years, with her wages given to Naboth Graves, the husband of Sarah’s daughter Irene.8

Rachel passed away on August 21, 1746, at the age of approximately eighty. Her death was noted by New London, Connecticut, resident Joshua Hempstead in his diary, which is full of all kinds of observations and local information. Hempstead noted that Rachel had “always lived in the family” ever since she had been taken captive in King Philip’s War in 1675.9 Rachel spent just over seven decades of her life in slavery. Hempstead notably described her as “Honest faithfull Creture [sic] & I hope a good Christian.”10 Dido passed away five years later, around the age of forty on December 6, 1751.11

As Rachel’s long and complex life shows, the enslavement of Indigenous people, whether in warfare or through judicial means, could radically alter the lives and realities of several generations. Continually enslaving the children was just one way that white New Englanders added enslaved Indigenous people to their households. Other methods included ongoing importations from other colonies, including the Caribbean, forced indentures, and debt servitude. Debt servitude was especially effective. Merchants and sea captains encouraged Native Americans to pledge credit in exchange for assistance with funeral costs, resources, etc., knowing that they often lacked the means to satisfy the debt. This often led to colonists forcing Natives to work for them for a set number of years or until their death, after which this labor could be inherited by the settlers’ children or passed onto offspring of Indigenous people.12

For further reading

Baker, Henry Augustus, History of Montville, Connecticut: Formerly the North Parish of New London from 1640 to 1896. Press of the Case, Lockwood & Brainard Company, 1896.

Di Bonaventura, Allegra. For Adam’s Sake: A Family Saga in Colonial New England, 2013.

Hurd, D. Hamilton. History of New London County, Connecticut. J.W. Lewis & Co., 1882.

Newell, Margaret Ellen. Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

We-Ha. “Simone, Hannibal and York: Enslaved in West Hartford.” We-Ha | West Hartford News, February 1, 2022. https://we-ha.com/simone-hannibal-and-york-enslaved-in-west-hartford/.

Footnotes

- Records of the First Church of Christ, Connecticut, 1670–1916, 2:101.[↩]

- For an Indigenous-centered history of King Philip’s War, see Brooks, Lisa, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War (Yale University Press, 2018).[↩]

- For a good overview of these processes, see Newell, Margaret Ellen, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Cornell University Press, 2015).[↩]

- Diarist Joshua Hempstead said she was taken captive during the “Narragansett War in 1675,” which is suggestive (King Philip’s War was rarely, if ever, called that). Hempstead, Joshua, Diary of Joshua Hempstead of New London, Connecticut, Collections of the New London County Historical Society, v. 1. (New London County Historical Society, 1901), 465.[↩]

- Binney, C.J.F., The History and Genealogy of the Prentice, or Prentiss Family, in New England, from 1631 to 1852. Boston, MA, 408. https://archive.org/details/historygenealogy00inbinn/page/n9/mode/2up.[↩]

- Hempstead, Diary of Joshua Hempstead, 212. See also Brown, Barbara W. and Rose, James M., Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 1650-1900 (Gale Research Co., 1980), 562.[↩]

- Binney, The History and Genealogy, 408.[↩]

- Brown and Rose, Black Roots in Southeastern Connecticut, 491–492.[↩]

- Hempstead, Diary of Joshua Hempstead, 465.[↩]

- Hempstead, Diary of Joshua Hempstead, 465.[↩]

- Hempstead, Diary of Joshua Hempstead, 580.[↩]

- Newell, Margaret Ellen, “The Changing Nature of Slavery in New England, 1670-1720,” in Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience, edited by Colin G. Calloway and Neal Salisbury (Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2003), 107–108, 125–126.[↩]