By Annette Lee, Khanh Vo, and Marija Blašković

Sometime between 1936 and 1938, George Fortman of Evansville, Indiana, sat down to recount his story of enslavement for the Federal Writers’ Project. The Works Progress Administration interviewer, Lauana Creel, was part of a team of federally-funded journalists who were sent out during the Great Depression to collect stories from formerly enslaved people. The typewritten version of Fortman’s account is one of more than 2,300 first-person stories in the Library of Congress.1 Most historical records were neither written by nor for enslaved Native Americans, so Fortman’s memorable recollection sheds light on the complexities of life in the American South while also pointing to the difficulty of discussing its darkest aspects.

Fortman’s great grandparents, John Hawk and Rachel, came from the Wabash Valley of Indiana. In 1838, following what turned out to be a decoy feast invitation, John Hawk, a “Blackhawk brave,” and Rachel, a Choctaw, were forced by the U.S. government to leave their lands and undertake a journey often referred to as “the trail of death” as part of wider forcible removals in the 1830s.2 When they finally reached Alabama, the exhausted couple and their daughters, Courtney, Lucy, and Rachel, were taken in by the enslaved population of Patent and Hester George and eventually themselves enslaved. However, within a couple of months, John Hawk became ill and died. Soon after, the George family decided to migrate from Alabama to a plantation in Kentucky to take part in the ironworks industry. They forced their enslaved population to accompany them, and Rachel, John and Rachel’s youngest daughter, died on the way.

As was all too common for enslaved people, sexual violence and rape plagued the women in this newly enslaved Indigenous family. Even before moving to Kentucky, Rachel Hawk gave birth to a son, Patent Junior, fathered by Patent George, patriarch of the George family. Meanwhile, Rachel’s eldest daughter, Courtney Hawk, gave birth to a daughter, Eliza, fathered by Ford George, son of Patent George.3 Years later, Ford also raped Eliza, who was his own daughter. When she became pregnant, Eliza seemingly avenged her rape, for Ford George was found dead, stabbed through the heart, and Eliza fled to the lowlands of Alabama. She was tracked down and forced to return.

Despite the resistance of family members, Hester George made sure Eliza raised her newborn at the estate. She apparently was never punished for killing Ford George. Hester named Eliza’s baby boy after her incestuous husband, yet at a later date he changed his name to George Fortman to leave behind this troubled association.4

Five years prior to the Civil War, Hester freed the enslaved workers on her property, but Fortman’s family members chose to stay and continued working for them, citing familial ties as one rationale.5 At a later point, Eliza moved away, but she could not make enough money to support her children. They were then bound out to different white families to work as servants or apprentices for a set term. According to his own testimony, George was bound out until he was fifteen years old, and then, thanks to his sister’s help, he spent a decade at the household of James Wilson, who often took him to see Eliza but also occasionally whipped him to ensure obedience.6

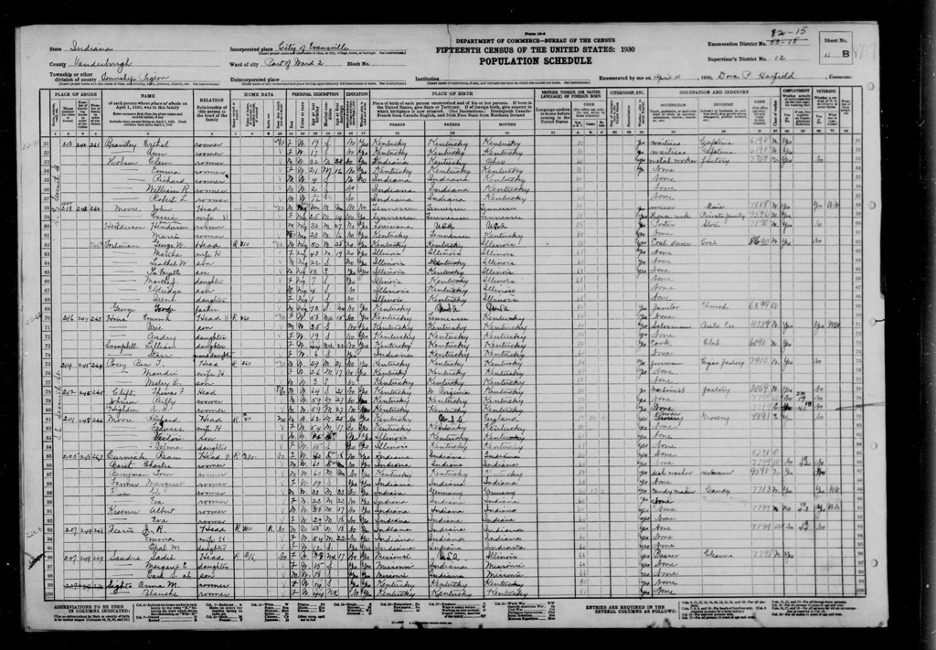

In 1883, George began working on his own. Over the years, he was a roustabout, cabin boy, cook, and pilot, in addition to holding a number of positions in river trade.7 Eventually, he was baptized and became a member of the Liberty Baptist Church in Evansville, Indiana, where he lived for over thirty-five years.8 In the 1930 census, this likely widowed 73-year-old church janitor is listed together with his son George W. Fortman, daughter-in-law, Martha, and their five children.9

The account of George Fortman’s family history is significant for several reasons. First, it shows the ways that enslaved Native Americans were present on American plantations, and for multiple generations, in ways that scholars have often overlooked. Second, his story is an important testimony of intergenerational sexual violence against enslaved Natives. Its full scope was rarely discussed,

as indicated by the lack of details surrounding the incestuous act or the highly euphemistic expression “birth of unsatisfactory circumstances” that George uses to refer to it.10 White owners and overseers raping their enslaved women was common as a strategy of oppression and as a means to secure more laborers.

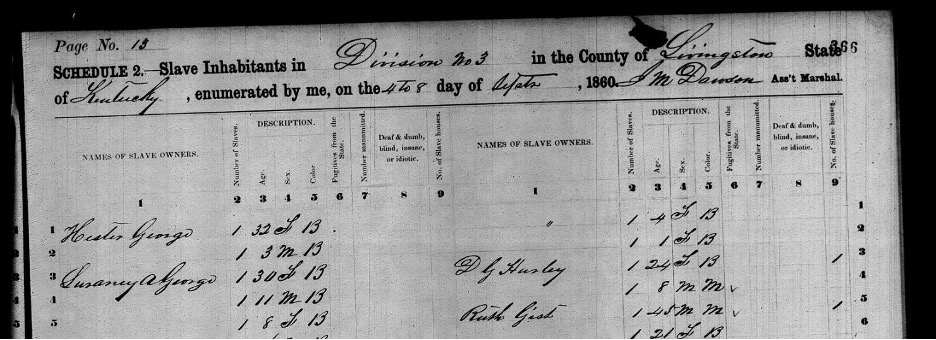

Fortman’s life also illustrates another common experience of Native American and mixed-race Indigenous individuals and families: that of racial recategorization. According to the 1860 Census of Livingston County, Kentucky, the three-year-old George Fortman was listed as “Black.”11

Moreover, the above-mentioned 1930 Census of Evansville, Indiana, described George as well as his younger family members in a similar way: “Negro.”12 The fact that George’s mixed ethnoracial ancestry was not properly recorded seventy years later serves as a reminder that we should be critical of the documented classifications, since “paper genocide,” that is, “intentional destruction of documents and records related to a particular group of people, usually with the intent of erasing their histories and cultures,” was more widespread than the used categories would have us believe.13

Regardless of the racial labels placed on him, George Fortman had retained a clear and firm sense of his family’s Native American ancestry and history, communicated through family oral traditions over multiple generations. Although the days of slavery and hardship were still fresh in his mind, the 1930 Census entry points to a noteworthy change: Unlike him, his son, and his eldest grandson, two of his school-aged grandchildren did receive some form of education. Maybe that is the image the old and eventually blind George had in mind when, at the end of his account, he referred to high school children whose voices would fill him up with joy: “They can build their own destinies, they did not arrive in this life by births of unsatisfactory circumstances. They have the world before them and my grandsons and granddaughters are among them.”14

Footnotes

- Federal Writers’ Project (FWP): Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 5, Indiana, Arnold-Woodson. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material, 84–95. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn050/.[↩]

- FWP, 5:84–85.[↩]

- FWP, 5: 87.[↩]

- This is according to the narrator himself; the 1860 census entry, depicted below, does not feature either of the names. It should also be noted that Patent George Junior, Rachel Hawk’s son, had his name reversed to George Patent before enlisting for the Civil War. See FWP, 5:89.[↩]

- FWP, 5:89.[↩]

- FWP, 5:92.[↩]

- FWP, 5:93. A roustabout is a manual laborer who works in broad or non-skill specific jobs.[↩]

- FWP, 5:94.[↩]

- “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch, Entry for George W. Fortman and Martha Fortman, 1930. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X4B1-7QV.[↩]

- FWP, 5:88.[↩]

- 1860 Slave Schedule in the U.S. Census Record of Livingston County, Kentucky, 13. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GB9J-99CM?view=index&action=view&cc=3161105&lang=en.[↩]

- “United States Census, 1930,” entry for George W. Fortman and Martha Fortman, 1930.[↩]

- Bullock, Chenae, “Black History Includes Native American and African-American Generational and Historical Trauma,” Cultural Survival (February 2, 2023). https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/black-history-includes-native-american-and-african-american-generational-and-historical-trauma (accessed February 19, 2025).[↩]

- FWP, 5:94–95.[↩]